So you do some googling and you find a bunch of companies that are in the business of bringing ideas like yours to life. You email a couple and they get right back to you. An enthusiastic sales person says your idea sounds great and they’d love to help. They email you a long, colorful prospectus full of glowing testimonials. The total overall cost for their services is a little unclear, but they will cover everything– patent, development, and production. You just need to wait.

And wait you do. You get occasional updates, most related to the patents being filed. It’s a little thrilling to sign the USPTO application paperwork. Then comes a bill for prototype preparation. It’s not that much– a couple thousand dollars– so you pay it. A few months later you get some line drawings, similar to the ones you gave the company when you explained your product, and another bill. It will be three thousand dollars per prototype, and they suggest you make ten or more to test the market. At this point you’re feeling a little impatient and it’s getting expensive, but you’ve been waiting a long time to get your product in hand and the patent has been filed. You pay up and wait. At this point, a few things may happen:

- You get your prototypes, make adjustments, and find buyers for your production run. All is good.

- You get a rough prototype or two, accompanied by a development bill for more work.You pay up and wait, repeating the process until you run out of money, patience, or both.

- You fire the company and are back where you started with a lighter wallet and no prototype or plan for production.

I wasn’t aware of any of this until I started getting calls from people in the third category, who were looking for a second opinion. Each one was a first time entrepreneur who had spent a good deal of their own money to develop a product and had very little to show for it. As the owner of a small design consultancy, I was baffled and annoyed. Who are these companies who promise so much and deliver so little? As it turns out, there is an entire industry of “Invention Labs” with slick websites, dozens of rhapsodic testimonials, and one star reviews on Better Business Bureau.

I’ve hesitated to write anything about scammy invention companies. It’s hard to frame it in a way that doesn’t look like an infomercial for my own design business at the expense of someone else’s. However, invention labs do two things I find beyond the pale: they take advantage of people’s best impulses, and they make the profession of industrial design look bad. The first is gross on a moral level, the second makes me personally mad. From a sense of legal caution and good manners I am not going to name names, but I do want to share some advice on how to avoid shady “design” businesses who rip off their customers and reduce trust in those of us who actually perform the services that they claim to.

Red flag one, and this may seem redundant, is fine print. Way back in 1997, the FTC filed the self-consciously named “Operation Mousetrap”. This targeted dishonest invention promotion service companies, forced them to reimburse scammed customers, and provide some level of transparency. Some of the older innovation labs have tiny disclaimers in the footer which say things like this:

“The total number of consumers in the last five years who made more money in royalties or sales proceeds than they paid to (Company), in total, under any and all agreements with (Company), is nine (9). This number includes people who first made a profit more than 5 years ago, if they continued to make additional profit during the past five years. The percentage of (Company) income that came from royalties paid on licenses of consumers’ products is .001%.”

Which should be enough to send anyone running for the hills. Others are more subtle, but any claims that are hard to verify or use nonspecific language should be treated with caution.

Red flag two is a firewall between you and whoever is actually working on your product. Someone in sales taking your first call isn’t unusual, but that shouldn’t be the only person you meet. Invention labs often use freelance designers* and engineers almost exclusively and do everything they can to keep their clients and designers from meeting. If you are at the point of signing a contract and still haven’t spoken to, emailed with, or even know the name of the person who will be doing the design and engineering, it’s cause for concern. Most design houses use freelancers, but the core team should be available to talk to you.

Red flag three is disingenuous metrics of success. Invention labs paper their websites with testimonials and success stories, but press releases can be bought, even in familiar publications like Forbes and CNET. Retail space can also be bought, and images of products on shelves does not necessarily indicate sales. What really tells you a firm is launching successful products is third party articles and long term retail presence, multiple SKUs and real-world visibility.

Red flag four is a stated ability to do everything. Good companies nearly always specialize: an industrial design studio won’t do patents, and a marketing company won’t do CAD design. This isn’t to say there are no reputable one-stop-shops, but it’s rarely an indicator of excellence.

Red flag five is a vague or confusing price structure. While it’s common for design studios to offer a range of numbers, especially with early stage projects, you should at least be given a rough idea of what the project will cost, start to finish, and how long it will take. Invention labs thrive on the sunk cost fallacy, knowing that after a large initial investment their clients will often be willing to keep paying fee after fee, in the hopes that this will finally get their project into the world.

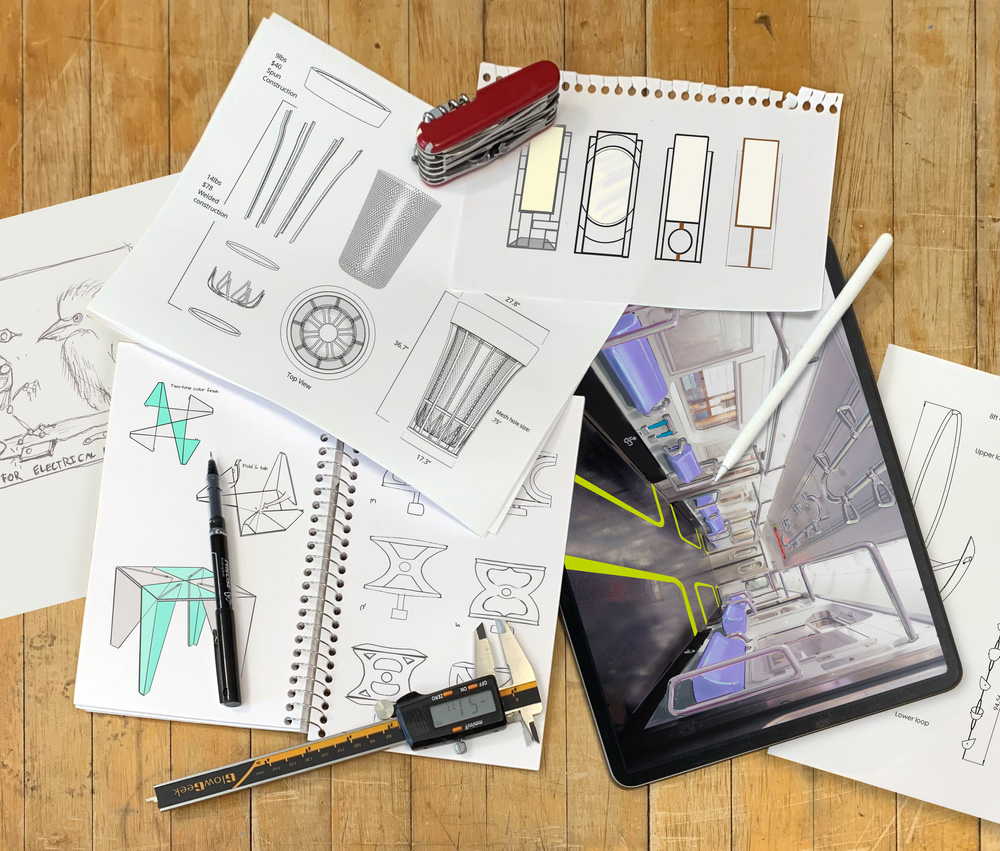

So what is an inventor to do? First, cast a wide net. Talk to small businesses, large businesses, established design houses and upstart engineers. Look for personal connection and a genuine interest, not just in your idea as it stands but how it might be made even better. Talk to previous clients and read reviews on third party sites. Make sure a plainly written contract, with clearly defined milestones and expectations, is in place before money changes hands. Meet the team and understand who is doing what. Make friends with the CAD person.

And if you do suspect that the firm you’re working with is more interested in taking your money than in developing a great product, and if this hunch is backed up by reasonable evidence, end the contract and spread the word. Innovation farms only exist because they are great at selling dreams, and exploiting the sunk cost fallacy when they cannot deliver. No good idea deserves to disappear that way.

*I was one of these freelancers many years ago when my business and I were young. It promised a lot and paid poorly, and I realized halfway through that I was not freelancing for a design team, but fully in charge of a project that I had been barely briefed on. Any questions I had about it were directed to the business, who then asked the client, who told the business, who told me. I wasn’t even allowed to know the name of the client, in case I should be moved to poach them. It was maddening, and I quit almost immediately.